Epistemically Challenged: Scott Harris

Epistemically Challenged is an opinion series about how each one of us explores knowledge. In this installment, airline pilot Scott Harris talks about the importance of teaching his children to think critically and deeply about the world.

In late April, on a night that was cool after a warm spring day, I was flying my passengers north along the eastern seaboard, on the last leg of a four-day trip ending with our arrival in Newark, New Jersey. It was clear and dark with only the glow of Philadelphia behind us on the right, and a faint hint of light from New York ahead on the horizon.

My first officer and I were chatting and remarking on the weather and smooth air at 31,000 feet, both looking out his right-side window at the coastline and the Atlantic Ocean, when something near the horizon caught our attention. It was yellow-orange and fairly bright though far away, and it flickered in the way a large bonfire might change its intensity as the flames move.

We stared for a few minutes, and I asked, “What do you think that is?”

“I have no idea,” he said, “but it looks like something on fire out there. Do you think it’s a cargo ship, or something like that?”

“Do you think it might be something with the military?” I asked.

As we progressed along our route and began our descent, the thing would disappear briefly then reappear in a slightly different shape, growing in size, still orange, still flickering.

“It almost looks like a fire that someone is trying to put out,” said my first officer. “Maybe we should let Air Traffic Control know?”

“I bet if it’s that big, someone has to know about it. I bet some other airplane saw it too, even if the Coast Guard doesn’t already know. Let’s wait and see if anyone else on the frequency says anything.”

I was being cautious, mostly because I didn’t want to embarrass us by re-stating what a bunch of other pilots had already stated, but also because I wanted to evaluate the situation and what we were seeing. It was so out of the ordinary that it seemed to warrant a little thought before we rushed to make a bunch of radio calls that might get a lot of people worked up.

“Make sure we are listening to guard (a dedicated emergency frequency) and see if there’s anything about it on there.”

We heard nothing on the emergency band after a few minutes and were still puzzled; but just as I reached my hand to the button that would transmit our concerns over the air traffic frequency, we both laughed. The “cargo ship fire” we had been watching was actually the moon rising low on the horizon, its reflected light scattered through the atmosphere, and from our position, mostly obscured by a low layer of marine clouds that had gathered in the cooling night air.

Although this incident happened months ago, I’ve told this story to my children many times. They are both 12 years old, a boy and a girl, and they think I’m a dunce. Any time we are out at night, and there’s a full moon, they ask if I need to call the fire department. They tease me—not because they really believe I’m dumb, but because I’ve raised them from the very earliest age to think clearly and critically and deeply about the world around them; they enjoy seeing their seemingly knowledgeable and worldly father fooled by something seemingly simple and obvious.

My challenge as a parent, as a grown-up with a science degree, and as a professional who works with physics and math in a simplified but practical manner every day, is to raise my children to approach life like little scientists. Every week I try to use a story like this to illustrate the pitfalls of irrational thought or uninformed decision making. Their future careers may have nothing to do with science (directly), but the scientific approach to thinking and reasoning will serve them well in whatever they choose.

But every week I also have to fight against school and the media to keep them thinking deeply and rationally. This is my battle, and what I see as the great challenge of those who work in science, the media and in education: how to get children (and, for that matter, adults) to look more deeply at the world around them, to indulge their curiosity, and to stop and think critically, which is to say, scientifically.

The problem of knowledge that I feel we all face today, and the one that I want to equip my children to deal with is that the world now knows so much more than they or any individual can possibly know. There was a time in human history when the world moved more slowly and it was possible to keep pace with advances in science and technology. The near-instantaneous flow of information in today’s world now allows science to build on itself quickly, almost exponentially in some cases.

The light-speed movement of electrons also means that the reporting of accumulated knowledge has to try to keep up, and it turns into a bullet-point bonanza, a summary of summaries and a regurgitation of Cliff Notes versions of information. While it’s nice to know a little bit about everything and seem knowledgeable, our comfort with this superficial understanding leaves us with a mere casual acquaintance with real knowledge. We read a story culled by some news aggregation software, six degrees separated from the actual events or research, and end up arguing with the produce manager at the supermarket because they are carrying GMO vegetables. I don’t want my children on either side of that grocery store debate, as customer or manager, unless they are armed with a real understanding of the issues.

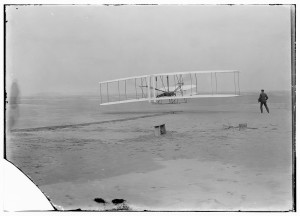

The Wright Brothers’ first sustained flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on Dec. 17, 1903. Image provided by Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

What I’d love to see my children doing is to move away from that bullet point level that is all around them, and spend a lot more time learning subjects in depth, especially at the middle school level, when they are now able to understand more complicated concepts. I’d love to see their classmates learning to respect depth—depth of knowledge, depth of expertise. In diving deeply, teachers have the opportunity to cultivate a love of learning among students, an appreciation for details, and a lifelong interest in asking ‘why?’ over and over—and having the satisfaction of finding the answers to those questions.

Instead of teaching every possible discipline in a science school year, we could, instead, teach some science—and a lot of disciplined thinking. We need to instill the ability to ask question after question (even when the answer seems obvious), to apply logic and use objective data in problem solving, and champion the idea that it’s okay to fail, because it’s the best way to learn. With these tools, kids could grow up to appreciate a news article longer than 200 words, or a comment longer than 140 characters. They could become adults who use the unprecedented wealth of knowledge at their fingertips to advance the cause of humanity. They can do all of these things if we teach them how to think instead of what to think.

Flying over Philadelphia that night, it is difficult to imagine a time in our history when people looked up at the sun and stars and the same fiery moon and believed that we were at the center of the universe. Copernicus looked at the heavens and questioned and thought deeply about something that seemed obvious and intuitive. When he did that, he turned the universe inside out.

The same processes were at work in the minds of a couple of bicycle shop owners from Ohio whose critical thinking and problem solving skills would take flight above a beach at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in 1903—and continue flying through thousands of minds all the way up to my now family-infamous, moon-on-fire flight, about which I am mercilessly teased. But I happily accept the teasing if it means that my children will learn from my mistakes, as I hope they learn from their mistakes and successes. I’d much rather have them grow up to be deep-thinking bicycle shop owners who know how the atmosphere effects our view of the heavens, than celebrity pseudo-scientists who, if looking at the moon floating just off the Jersey Shore on a clear night, would be content to shout “fire!” and leave it at that.

— Captain Scott Harris lives in Washington DC, and flies for a major airline based in Newark, NJ. He has logged nearly 10,000 hours of flight time, but when he’s not in the air, his favorite activities are terrestrial: playing the guitar, engaging in witty banter with his 12-year-old twins, and watching the Baltimore Orioles.