How data journalism helped power a rural broadband revolution

One small magazine, one semi-retired reporter, and an award-winning series of studies using federal statistics that showed why broadband was critical to rural survival.

Trevor Butterworth

June 17, 2019

Photo credit: adapted from image by Rostislav Sedlacek for istockphoto.com

“W

e are doing broadband,” said President Trump on signing H.R. 2, the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (aka, the “Farm Bill”). “Everyone wanted it so badly.”

Hardly anyone noticed, but to advocates of rural broadband, it seemed scarcely believable that wanting something so badly had actually ended in the funding to make it happen. But there it was: $1.75 billion over five years—which was coming on top of $600 million for rural broadband in the March 2018 omnibus budget bill.

Behind the wanting, though, was data—and notably, a series of studies looking at the impact of broadband access on rural population loss, and showing, over several iterations, an increasingly causal link between lack of access and population loss in America’s most disconnected counties.

The studies were done for a small business to business magazine, Broadband Communities, and its Editor-at-Large, veteran data journalist Steve Ross, who had taught students at Columbia’s Graduate School of Journalism for years about the value of looking at the data (including this writer in 1997), when data journalism was called “computer assisted reporting.”

Regulators had been headline attendees at the magazine’s conferences, so the studies were widely known and shared within the broadband community; but it was a series of calls from congressional offices in 2018 to talk about the findings that led Ross to think they might be helping to inform legislative change. As Ross notes, congressional staffers were “shocked” to discover that the studies came from an independent trade magazine and not an industry front group or advocacy organization.

What this story shows is that even a small magazine can help drive the kind of change that affects millions of Americans. And it did so, because a journalist knew how to use federal statistics to tell a story.

A “cyberbridge to nowhere”?

On Feb 2, 2009, just before The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was passed, the New York Times ran a front-page story warningthat President Obama’s plan to provide money for rural broadband “could just as easily become a $9 billion cyberbridge to nowhere, representing the worst kind of mistakes that lawmakers could make in rushing to approve one of the largest spending bills in history without considering unintended results.”

Ultimately, $7.2 billion—1 percent of the stimulus—was earmarked for broadband, half for new trunk lines, and half for consumer-facing networks. Around 2,000 communities and small operators applied for grants and loans to build local networks, and an enormous amount of middle-mile network was built as well. As the term suggests, middle-mile is the part of the network connecting last mile consumers to the major telecommunications carriers. This was the “cyberbridge” that had to be built if rural America was going to get meaningful broadband access, and the nation, as a whole, was going to rise from its 15thplace global ranking on Internet access.

ARRA may have confounded the New York Times’ prognostications, but by 2014, it had run out of money—and millions of rural Americans were still without broadband access. Ominously, major carriers had stepped up their lobbying efforts with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) to promote state restrictions on municipalities building their own broadband networks.

It wasn’t that ALEC thought rural broadband was a waste of time. It publicly promoted fast Internet connection as “critical to improving the nation’s long term competitiveness in a global market, and to achieving certain socioeconomic improvements in the quality of American Life;” it just believed that the best and only way to do this was to leave this transformation to the network carriers, which it believed were doing a “phenomenal” job. Municipalities shouldn’t be in the business of using taxpayers’ money to build networks.

The flaw in ALEC’s argument was that much of this rural, “last mile,” network wasn’t economical for major carriers to build. Municipalities didn’t really want to be in the business of building broadband networks either, but a loan from the USDA’s Rural Utilities Service could reduce the cost to the point where a network could be financed and then rented out to a carrier and break even. The benefit to the municipality would be what followed from better Internet access.

Nevertheless, the idea that states should stop their own municipalities from applying for loans and grants from the USDA began to have an impact. But even municipalities that didn’t face these kinds of legislative roadblocks had to face other economic obstacles. Small community banks were simply too small to provide the kinds of loans needed to build networks—and even where they did, the economic argument increasingly became one that, as rural counties were losing population, it just didn’t make sense to risk money on building or upgrading their broadband networks.

To Broadband Communities, this statement was unproven. What if rural communities were losing population becausethey lacked decent broadband access? It was against this confluence—ARRA stalling, prohibition increasing, and banks shrugging—that the magazine set out to answer this question—one that was critical to its readers and advertisers. If the banks were wrong, there were business opportunities. In 2014, it embarked on a series of studies to see whether there was an economic case to be made for rural broadband.

The first study: Did broadband quality lead to county population change?

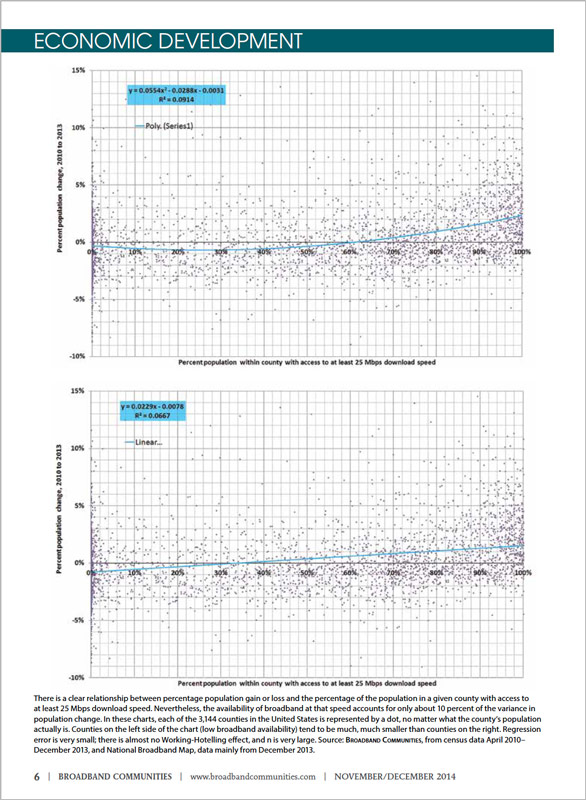

One useful if imperfect asset was the National Broadband Map, which was mandated by ARRA on the principle that all Americans should know what kind of service they were getting (and a useful reminder that public data goods are essential to spurring competition in services). Taking population data as a proxy for job growth, because it was likely to be more accurate and timely than county-level job data, Ross compared the Census population data for all 3,144 counties with broadband quality available in those counties according to the National Broadband Map.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) defines broadband as 25 x 3 Mbps, which Ross says is reasonable. But he also ran the data for a dozen other definitions. All followed a similar pattern within each state: Between 2010 and 2013, counties that lost the most population had either “lousy” broadband or no broadband, and broadband quality was associated with 10 percent of the population variance – a big effect to find in a quick-and-dirty first test, and one worthy of more study in order to see if lack of broadband was a causing the loss.

For that, Broadband Communities won top regional honors for original research by a business magazine in the American Society of Business Publications Editors (ASBPE) awards.

Results from the first study

Results from the second study

The second study: Establishing a causal relationship between broadband and population change

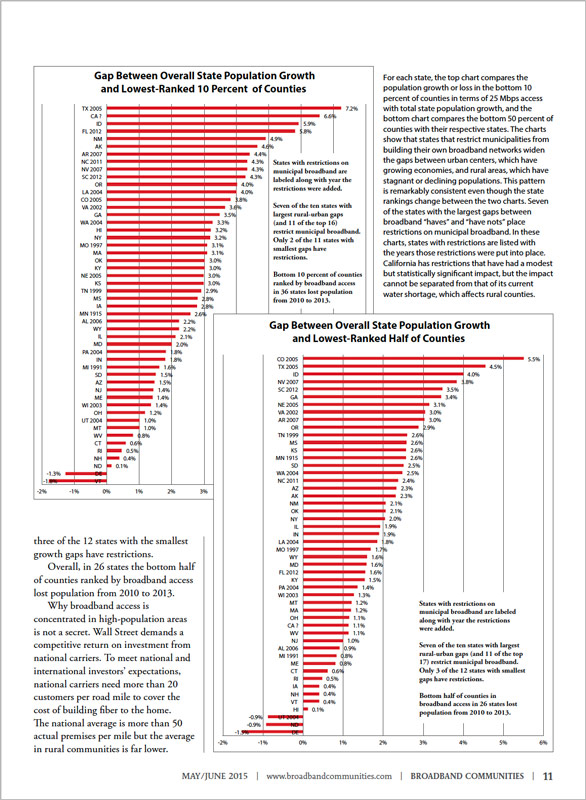

“We wanted to show causality,” says Ross, and the way to do this was to compare counties in the 19 states that restricted municipalities from building their own networks with counties in states that had no restrictions.

This analysis was more complex: Some states had been prohibiting municipalities from building broadband networks for a long time; others had only begun to impose restrictions. Some restrictions were mild; others, especially those driven by ALEC, draconian. There was also the fact—gleaned from the magazine’s reporting over the years—that a municipality which threatened to build its own network often prompted the local service provider to upgrade its service.

Still, at the time there were 150 public broadband systems in the U.S., and a further 100 public-private partnered systems; there were 19 states with serious restrictions on public broadband and 30 with none. “I figured we had enough statistical power,” says Ross, and the results blew us away.”

States that restricted public broadband were losing rural population at three times the rate of states that didn’t have prohibitions—even though the prohibition states tended to have larger overall population growth. Moreover, further analysis showed that when you compared counties where farming, manufacturing, and low employment were the defining economic activities (or inactivity) in restricted states versus non restricted states, the latter’s populations either gained population or lost it more slowly. Among the seven rural county classifications tracked by the US Department of Agriculture, only mining counties showed no relationship between population loss and restrictions on broadband.

Eventually, the articles garnered eight regional and national awards from the American Society of Business Publication Editors, including a second place nationally for original research by a business or professional magazine. This, for a publication that, at the time, had 1.5 editors—with Ross, working half-time, being the 0.5.

With business success, the staff has grown. “My colleagues worked extra-hard because I was spending several months each year diverting attention to the project,” Ross says. “That’s only realistic in a close-knit group dedicated to readers, and that includes the late Scott DeGarmo and his widow Barbara, the majority shareholders.”

The FCC’s Gigi Sohn, who worked directly for Tom Wheeler, FCC chief in the Obama Administration, said the research had gone further than any other study.

What impact will H.R. 2 have?

“It’s huge,” says Ross. “It’s huge—and it’s the right kind of federal aid.” Every dollar USDA gives or loans to rural broadband will lead to three more dollars of construction, and this, he explains, will end up generating $8 billion in network construction over the next five years. “That’s far more than the original stimulus bill did. Republicans get a chance to prove they’re actually doing something for rural areas, and the Democrats are happy to go along with it because they also want more economic development.”

The one group that has missed out on the story of rural broadband is the major news media, which has irked Ross, the veteran journalism professor, no end. It doesn’t just reinforce the perception of a rural-urban divide in media coverage, it also points to a class system in journalism where trade publications are looked down upon because they’re niche concerns or their focus is on “business.”

Yet because a trade publication has to understand its audience or it dies from a lack of credibility, it has an incentive to provide analytical depth and accuracy. That’s how it best serves its readers. As Ross keeps noting, “We were trying to tell our readers ‘here’s where’ you might want to build broadband—here’s your opportunity. We weren’t treating this as advocacy, we were treating it as a business proposition for our readers and our advertisers—companies you’ve probably never heard of before, like Calix and Adtran, or until more recently, Huawei.”

Perhaps even more irritating, some journalists regretfully told Ross they couldn’t cover his findings because they weren’t the result of peer reviewed academic research, or research by a foundation, a test, ironically, he had suggested to students when he taught full-time at Columbia, but one formulated before the rise of data journalism as something news organizations do as a matter of routine reporting.

The question here is, where does data journalism end and scientific research begin? There is no formal peer-review system for data journalism, and often very little transparency as to where the data came from and how it was analyzed. On this score, the Broadband Communities study was an open rather than a black box: It would have been easy for a major news organization’s data journalism team to replicate the findings—or, at the very least, check them out with a statistician. Many peer-reviewed studies do not provide such data.

It also helped that Broadband Communities was upfront with its readers about the uncertainties in its research: It included a long list of confounders and often published two defensible analyses of the same data when they showed different results. “It really helps the readers understand the risk and uncertainty—our readers and advertisers are bright, and willing to risk capital,” says Ross. “But they are not, generally, rigorously trained in statistics. My goal is, of course, to do good, but the data kinda defines what good is.”