Death by Bacon: Did the News get to the Meat of the Matter?

The conclusions were guaranteed to make headlines around the world: processed meats, such as bacon, were carcinogenic—and red meat was a “probable” carcinogen. The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer had surveyed over 800 studies on the issue and announced its findings in The Lancet Oncology—although the actual meat of its analysis, so to speak, would have to wait for the monograph, currently in press.

Few media sources understood the implications, or wanted to contextualize them. “Ham, Sausages Cause Cancer; Red Meat Probably Does, Too, WHO Group Says,” was the headline at NBC News—one of thousands of similar stories which ultimately led to the WHO issuing a later clarification on eating meat, a fact that got much less coverage than the original report. Next year, apparently, it will contextualize their findings in terms of a whole, healthy diet. One year too late, as far as media coverage goes.

While initial stories served up doomsday claims about bacon and its cousins, some of the subsequent coverage was remarkably good and explained some of the subtleties by looking at the following issues:

Wonk media—a defense against alarmism (and IARC’s disastrous science communication)

If there was a silver lining to “Death by Bacon,” it was—as Rebecca Goldin notes—the wave of reporting that went behind the International Agency for Cancer Research’s headlines and asked what exactly the agency meant in terms of risk. “There is a move in journalism to be thoughtful, analytical and evidence based about science and science risk stories that this was one heartening example of,” said one of America’s top experts on risk communication, David Ropeik. He also noted the “terrific, wonderful piece on Cancer Research UK,” which explained the story in a series of infographics.

But none of this absolved IARC from sowing confusion in the first wave of news reporting. The agency needed to be much more clear in explaining the difference between the relative and absolute risk, the way it classifies carcinogenicity, that their evaluation “is not a prescription for how people should actually behave, and that their evidence is a hazard based risk approach not a full risk assessment, which includes hazard and exposure,” he said.

“They’ve made this mistake before; by now, they should understand that they need to make these qualifications clearer, higher, sooner, and louder, so that the wave of first stories don’t do as bad a job as they do.”

“Frankly, said Ropeik, I think we have a right to be frustrated that they haven’t learned lessons from the past about the need to do this. Gosh, out comes the glyphosate thing, or out comes the cell phones and radiation thing, or out comes anything with the c word attached to it—cancer—and the same thing happens.”

Another risk expert concurred. Dr. Adam Burgess of the University of Kent, pointed to the unhelpfulness of IARC framing the association between meat consumption and cancer “as personal risks that increase an individuals’ chance of harm by x percent.”

“These,” he emailed, “are aggregate figures that have little meaning for the individual, and it is far more useful to think in terms of absolute rather than relative risk. Using what Gerd Gigerenzer calls ‘natural frequencies,’ percentage increases in risk mean a—usually small—increase in the numbers affected, from, say five people out of 100 at risk of a particular form of cancer, to six. Less dramatic perhaps; but all the more useful for it. IARC’s headline making would be more credible were they also to communicate risk in this kind of way.”

A slightly different take came from Professor David Just, an expert on behavioral economics at the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University, who said that because most food consumers don’t differentiate between causality and risk, their intuitive grasp of the risk from processed meat was at odds with IARC’s findings. “For this reason, many believe such designations are alarmist or exaggerated and feel they can discount them. Essentially, everyone they know eats this food and they don’t observe unreasonably high rates of cancer in their mind and so they believe the finding is biased,” he emailed.

“I tend not to think that [the IARC announcement] will cause panic, so much as apathy. The subtle difference between causality and risk is difficult for people to process given their limited attention span for news. I do think the more they cite the original data and make the case clear it becomes easier for people to both believe and understand the nuance. (We see this with info about GMOs too). However, this is not easily done in the standard news outlet.”

TB

Carcinogenicity A number of news organizations called for calm in the wake of Death by Bacon. Mashable, in telling us not to panic, included an excellent description of the distinction between the confidence with which we conclude something is carcinogenic, and the level at which it is carcinogenic.

The Atlantic explained carefully what the IARC rating of “carcinogenic” means. An IARC rating of Group 1 means that the substance has been established as carcinogenic to humans; it does not, however, explain how carcinogenic. There are substances that would kill anyone who comes in contact with them, and others that have little chance of affecting anyone’s life. The IARC ranking, however, does not make this distinction: carcinogens are carcinogens.

Vox provided an excellent walk-through of a map of carcinogens according to the IARC, making clear that the certainty with which we can say that something causes cancer is a wholly separate question from evaluating the actual risk.

Absolute versus relative risk.

Absolute risk is the actual risk we undertake, without reference to a baseline risk. Relative risk, however, is inherently a comparison. If, as the IARC analysis contends, eating 50g (1.7oz) more of processed meat results in an 18 percent increase in risk, the authors mean 18 percent of the risk we already have—which is much smaller than 18 percent itself.

Mashable included an excellent discussion of the difference between an increased relative risk and an increased absolute risk of cancer, complete with an example of how to calculate the relative risk. If the risk were 10 percent of getting colorectal cancer, then an 18 percent increase would result in 18 percent of 10, or a 1.8 percent increase in absolute risk, bring the risk from 10 percent to 11.8 percent.

While Mashable used a hypothetical number, less than 5 percent of the U.S. population will, in fact, be diagnosed with colorectal cancer in their lifetimes. With the 18 percent increase, we should expect an 18 percent increase of this 5 percent, which amounts to moving the needle from 5 to approximately 6 percent of the population who will get colorectal cancer, if their consumption of processed meat were increased by 50g per day for the rest of their lives.

Buzzfeed got the absolute percentages right, mentioning that the UK’s National Heatlh Service puts the lifetime risk of colon cancer at 5 percent, and the increased relative risk resulting in an additional 1 percent of risk.

The Comparison to Cigarettes

Many news organizations pointed out that comparing eating meat— even a lot of it—doesn’t really compare to the cancer risks from cigarette smoking.

While a 50g increase in processed meat (a couple of slices of bacon) a day amounts to an 18 percent increased risk of colon cancer (and 35 percent of such cases result in death), an increase in a few cigarettes per day results in about a 200 percent increased risk of lung cancer for men, and a 400 percent increased risk for women.

This insight on light smoking research came from the Huffington Post, who jokingly referring to themselves as the preserved meat apologists, while affirming the inappropriateness of the comparison between eating processed meat and smoking.

Many other news organization spoke to the risks of smoking regularly, including a mention in Buzzfeed of the 2400 percent increased chance of lung cancer if you’re a male smoker (smoking a pack a day or more) compared to a nonsmoker. This percentage puts the 18 percent associated with 50g of processed meat to shame. Even if someone ate 200g (about 7oz) of processed meat per day, there would only be a 72 percent increased risk (assuming the risk estimates are linear). Vox made a similar comparison—also noting that the Centers for Disease Control estimates that smokers get lung cancer 15 to 30 times as likely as non-smokers.

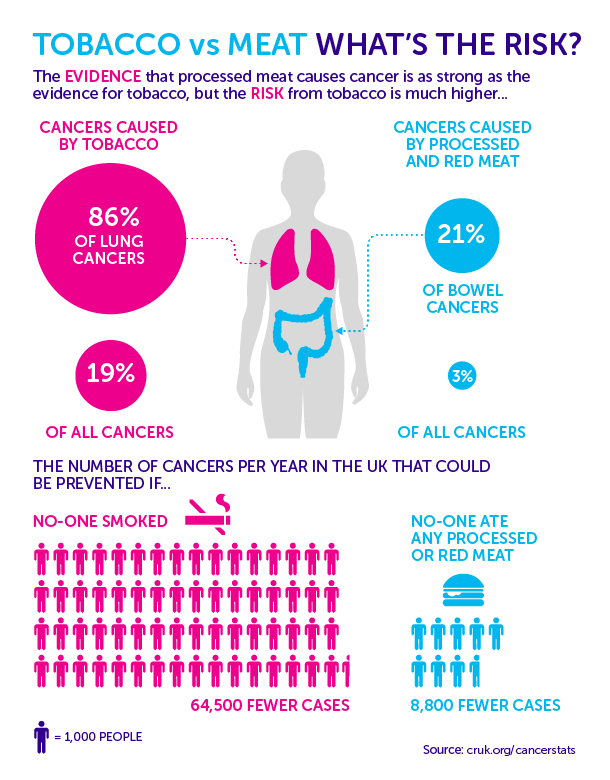

The Guardian and Buzzfeed both provided the same beautiful graphic from Cancer Research UK showing the numbers of cancers that could be prevented in the U.K. by eliminating smoking and by eliminating all processed meat. Smoking cessation would result in a whopping 64,500 fewer cancer cases per year—more than seven times as many as the expected reduction of 8,800 fewer cases if there were no processed meats in the UK diet.

Why are the actual numbers of death so important? Well, if smoking were to increase many-fold your risk of cancer but that risk was, in absolute terms, extremely small, then the risk of smoking would still be small. Unfortunately, the numbers are not that small—even at a population level, smoking is far worse than eating processed meat.

Bringing in Other Science

The Washington Post’s Wonkblog presented a fascinating twist on the story, noting that your risk depends also on your DNA. Some people’s genetic make up make them significantly at risk for cancer through products liked processed meat, and some were essentially immune. This raises the specter that the IARC studies—including huge amounts of data from around the world, may have been dirtied by being put into one pool for a single conclusion; rather than an 18 percent increased risk due to 50g more meat, it may be that some people can eat a huge amount of meat with no increased risk, while others may be at far greater risk from increased consumption, based on their genetic profile. It’s only when the groups are put together that we see the 18 percent rise per 50g of processed meat.

Asking the right questions

How could the rush to publish have produced smarter reporting? Here are some the questions that should have been asked at the start:

- What does the classification mean?

- Are the risks absolute or relative? Evaluate them in absolute terms for the reader.

- If an agency compares two risks (such as eating processed meat and smoking), in what ways are they comparable? Be specific. In this case, they were comparable in terms of how sure scientists are that they are carcinogenic, but not in terms of how carcinogenic they are.

- Is the increase attributable to the causes cited by the agency? In this case, the clear message from IARC is that there is good evidence that processed meat causes cancer?

- Put the results in context: what other research relates to these results? What other risks are comparable to the ones mentioned here?

The news coverage on this topic mentioned here attended to each of these issues except perhaps the last one. Are there other risks that we take in our lives, comparable to eating 50g of processed meat each day? Apparently, dying due to a motor vehicle incident has a similar risk over the course of our lifetime in the U.S., according to the National Safety Council. It’s a risk many of us are willing to take.

Please note that this is a forum for statisticians and mathematicians to critically evaluate the design and statistical methods used in studies. The subjects (products, procedures, treatments, etc.) of the studies being evaluated are neither endorsed nor rejected by Sense About Science USA. We encourage readers to use these articles as a starting point to discuss better study design and statistical analysis. While we strive for factual accuracy in these posts, they should not be considered journalistic works, but rather pieces of academic writing.

Deaths are not the same as cases. And low impact cases, where you don’t suffer and survive are not too worrying.

“Why are the actual numbers of death so important? ” you say, right after talking about the number of cancer CASES. I had to search back in the text to see ” (and 35 percent of such cases result in death),”

You have to be careful, cos in some medical problems the number of cases can be high, but that doesn’t convert to a high number of suffering or high number of deaths.

I view the smoking comparison as a convenient strawman argument for people ‘fighting the hype’ they perceive. I didn’t laborously go through many of the media reports, but it’s my impression that most made it very clear that (WHO/IARC)made a qualitative categorization, not a quantitive one( i.e. an absolute risk ascertainment).

If the public only reads the headlines, I guess your’s and other critiques would be more on target, but then I would put the blame more squarely on media/reader.

Furthermore, and this will probably not go down well with you guys, but this article is a classical example of scientific reductionism, and in the wrong way. Comparing lung cancer rates with colorectal cancer rates is false equivalency. More meat/animal based diets are associated with a myriad of other disease risks. CVD, diabetes, weight etc. Also other cancers.

It’s also the case that given the design of these epidemiological studies there’s a tendency for regression towards the mean, as well as the overadjusting by other factors, weakening the real effects. Ecological studies show manyfold lower mortality/incidence of colorectal cancer, which in my eyes is mostly linked with diet factors.

What I see in much of mainstream science culture underscoring the risk potentiality of various diet factors on disease risk/mortality should be a thing of the past. Tobacco has a much smaller impact on morbidity/mortality than diet factors. (http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/#)

More animal-based foods is an important part of the unhealthiness of the modern diet, if you ask me. Of course my opinion has nil weight, but the totality of current evidence could suggest something close, and the possibility that this is correct should weigh heavier on people’s minds before proclaiming things relatively safe, in an absolute sense, based on a reductionistic framework.

By the way, I may not contend with the view that the typical Westerner *only* increases colorectal cancer risk by 18% by 50g increased proc. meat intake(all other risk factors equal) and that this risk may not be very significant for most people. But the point was that this misses a bigger context.

“Bacon eating causes a 18% increase in the risk for colon cancer(RR 1.18).

1. Let’s say the increased risk was 20%(RR 1.2).

Does that imply that if a bacon gets colon cancer there is a 20% probability that cancer was ’caused’ by bacon?

It can not mean that 1 out of 6 bacon eaters colon cancers was 100% ’caused’ by the bacon and the other 5 were 100% not ’caused’ by bacon.

Is it not correct to say that, since the 1 in 1.2 is 83% of the total risk, there is an 83% probability that a bacon eater’s colon cancer was probably ’caused’ by factors other than bacon?

2. Since colon cancer is a somewhat rare disease with an incidence rate of only 42/100,000 people,would it not be useful to look at the relative risks for NOT getting the disease?

There are, after all, over 2,000 people that do NOT get colon cancer each year for each one that does get it.

Are none bacon eaters 20% more likely to NOT get colon cancer?

Let’s say the 42/100,000 rate is for the non-eaters.

That gives us 99,958 per year that do NOT get the cancer.

Bacon eaters would have a rate of 50/100,000 with 99,950 per year NOT getting the cancer.

99,958 divided by 99,950 = 1.00008

The non-eaters are only 1.00008 times more likely to NOT get colon cancer than the bacon eaters.

For all practical purposes, bacon eaters have the same probability of NOT getting colon cancer as the people that never eat bacon.

WHO forgot to mention that little tidbit.