George Washington, Data Scientist

By Scott Harris

George Washington was not a scientist, inventor or philosopher in the mold of Franklin or Jefferson; he was not a legal scholar as John Adams, or a grass-roots organizer like Samuel Adams; yet Washington was a man who valued reasoned thinking and the practical application of data analysis. Despite their storied, and incredibly accomplished lives, none of those other men grew and changed quite the same way as Washington did.

Reasons abound for his evolution, but lacking a formal education as Jefferson or Adams received, and without time to dedicate to purely philosophical pursuits, Washington’s early practical training in science and math gave him a grounding in scientific thinking and an appreciation for gathering and using data that aided him throughout his life.

Washington’s iconic status makes him harder to relate to than other founders who may be more easily placed in the context of modern society, but his ability to assess situations and people, his ability to remove emotion from important decisions, and his objective, scientific approach to problem-solving makes Washington relevant and worthy of study in any age.

Developing An Appreciation for Data

When Washington was 15 years old he wanted to join the Royal Navy. Fatherless, and like many young adults of that age, he was searching for his path in life and a way to make his mark on the world. The problem was, his mother wouldn’t let him join the navy; like many mothers, she wanted her son close to home.

Living in the world of Tidewater Virginia, where owning land, a farm and eventually an estate was the ultimate measure of a true gentlemen, and with a deeply rooted desire for self improvement, the young Washington found a way to connect with the landed gentry he admired and earn some money in the process. He studied as a surveyor, and in 1749, at the age of seventeen, became the youngest official surveyor of Culpeper County, a position appointed by the Royal Governor.

Surveying in the 18th Century

The surveyor of 18th Century Virginia had none of the modern surveying tools that are in use today, such as GPS, 3D scanners or digital levels. Using mathematics developed in the 3rd Century AD, tools from the 1500s, and a lot of deductive reasoning and brain power to solve complex spatial problems. A coveted position that required strict attention to detail and the ability to take accurate measurements, the professional surveyor was essential in resolving land disputes, legal cases involving Royal patents, and planning military operations.

Some basic tools were needed by the surveyor. A compass, Gunter’s chain and some plotting instruments were all that was needed to start. From there, it was an exercise in sheer brain power, requiring spatial awareness, detailed record-keeping, and mathematical skill. America in the 1700’s was a land in constant state of flux, heavily forested, inhabited by often hostile native peoples, with a landscape continually being altered by settlement and farming. A surveyor had to navigate this terrain, determining his position with frequently inaccurate maps, and using astronomical observations, then begin the job of creating a plat. Without the network of previously measured and determined survey points you may see in your city, the 18th century American surveyor had to assess the terrain, develop a plan for creating a plat (essentially, designing an experiment), find the lines of sight and then begin the process of laying out the experiment and taking measurements.

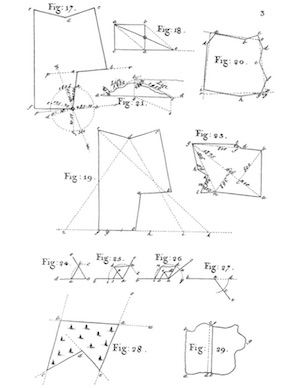

The ability to collect, record, process and interpret data was essential if any degree of accuracy was to be obtained. This practical application of mathematics and trigonometry required problem-solving skills and analytical thinking, as this excerpt from “The Practical Surveyor” will attest. A classic text by Samuel Wylde, published in 1725, it is quite possible that Washington owned a copy.

Image from Samuel Wylde’s “The Practical Surveyor” published in 1725. Click to enlarge.

Surveying required skills that Washington already possessed or came naturally—a strict attention to detail, the ability to notate data accurately and meticulously—and some that he would have had to learn or refine on the job, such as geometry, advanced mathematics, and natural history. The methods and scientific principles required of a surveyor fit his personality perfectly, and set the stage for the development of a life of data analysis and scientific thinking, As the historian Ron Chernow puts it, “for the rest of his life, Washington was stamped by his practical experience as a surveyor.”

As he moved from surveyor to Captain in the Virginia militia and took command of troops, Washington’s need for information grew exponentially, and he wrote often to the Governor lamenting his inability to effectively manage the troops when defending the frontier without accurate maps and intelligence. Washington saw the value of clean, objective data; and the muddled reports and inaccurate information coming his way often led to a loss of life.

By age 30, Washington had left his early military career for the life of a gentleman farmer, married Martha Custis and was living on the estate he inherited from his half-brother Lawrence. Faced with repeated tobacco crop failures, fisheries to oversee, products to import and export, and a large group of servants and slaves to manage, he saw that he could not be successful in this wide-ranging world without data, and lots of it. He required precise accounts of all activity at Mount Vernon and, as with any good experimenter and manager, knew that “system in all things is the soul of business.” One ledger entry noted 679,200 herring delivered in May of 1771. One can imagine Washington instructing his overseers to make sure that over half a million fish were counted accurately.

But his approach encompassed more than straightforward accounting. He conducted experiments with crop rotations, with different varieties of tobacco, and with various farming techniques. He read avidly the farming treatises of the day, and with each season, kept meticulous records, using the information to avoid mistakes of the past, eventually coming to the conclusion—ahead of most of his contemporaries—that tobacco production was not to be the future of a successful Virginia plantation.

Washington was away from his estate from 1775 until 1781. During that time, he went through a number of managers and overseers. He wrote letters constantly, requesting accounts of work completed, barrels of product shipped, and gave minute instructions on how he wanted the plantation managed. When his overseers failed to comply, Washington scolded them, and often replaced those who were unable to meet his exacting standards.

As manager of the estate, he knew, as we do today, that no large enterprise can survive without a thorough understanding of each and every aspect of the operation. As many great leaders through history, he was detail-oriented to the extreme, craving data of all kinds, and most importantly—and here’s the difference between Washington and some other, more traditionally educated founders— he knew the value of a proper interpretation of the data. Numbers alone meant nothing; it was their relationship to the world from which the numbers derived that made the difference between wins and losses, both in the account books, and on the battlefield.

A Scientific Approach to War

What we see in Washington’s eight years at the head of the Continental Army is a process of increasing reliance and need for data, and his interest in details went far beyond the usual need for estimates of troop strength, powder stores, and food supplies. The urge to know every detail sometimes resulted in overly complex plans that were impossible to execute, but the times that he had incomplete information always resulted in the heaviest losses. In attempting to defend New York against an assault by the British Army, a failure of intelligence about the roads and passes in Brooklyn saw the Continentals routed and forced into a midnight escape and a long retreat. New York stayed in British hands until the end of the war, and Washington, although failed by intelligence at later times, never forgot the lesson that what he didn’t know could hurt him.

As many great generals, Washington took the collaborative approach to leading his men. Councils of war meant debating options and conflicting opinions, leaving the General to take in all the available information, evaluate it in context of his own knowledge, and reach conclusions. What is more scientific? Moreover, he always made an effort to be objective. When facing down the British occupation of Boston, Washington desperately wanted to make an assault on the town, and was repeatedly convinced on the basis of evidence, and opinions of those in the field, that such an attack would be disastrous. As Alexander Hamilton noted after the war, Washington “consulted much, pondered much; resolved slowly, resolved surely.”

Washington served without pay as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, asking only that Congress pay his expenses. Upon resigning his commission after eight years of war, he submitted his expense account for review. The total spent was $160,074. When audited by the Treasury Department, it was found to be off by only 89/90 of one dollar, an error of .0006 percent.

Washington, The Man

Where Washington’s appreciation for information, data and the scientific method truly shines, is in ultimately in the development of his character. In Washington we see, a person willing to change into a better person – something one cannot do if one’s mind is closed. Always eager to learn and improve himself, he used information and knew the value of observation and self analysis to rise above mistakes, noting that “some men will gain as much experience in the course of three or four years as some will in ten or a dozen.”

His early life in Tidewater Virginia acculturated him to a stratified society, where one would look down their nose at slaves, at servants, at their social inferiors. When, after riding to Boston to take control of the rebel army in 1775, Washington faced the prospect of free blacks joining the Continental Army, he wrote “Neither Negroes, boys unable to bear arms, nor old men unfit to endure the fatigues of the campaign are to be enlisted.” And yet, he changed his mind when faced with evidence that black troops were neither less brave nor less skilled in battle. Driven by evidence and building upon the thinking of others, he accumulated a wealth of information about slavery and the people held in bondage, and ultimately changed his mind about the very nature of slavery itself.

When a freedwoman poet, Phyllis Wheatley, wrote an inspiring set of verses about General Washington and all that he meant to his country, he went so far as to invite her to his headquarters for a visit, signing a letter to her as “your obedient and humble servant.” This came from a man who grew up in a society that assumed African people had no ability to read or write. Once an aloof, even snobbish Virginia Gentleman, he came to appreciate the value of all people, the ultimate validation of the Revolution itself. It is hard to say that none of his growth and development would have happened without it, but from our perspective two hundred and fifty years later, we can see that Washington developed the ability to see beyond the insular world of his youth. The shedding of prejudices is perhaps the surest sign of a mind open to evidence; and as evidence mounted, Washington saw the inhumanity, the hypocrisy of holding people in bondage, and at the end of his life, set free all the slaves he could legally manumit.

A Scientific Legacy

George Washington was a man of great internal passions, his rage legendary, his emotions deep: a maid “frequently caught him in tears about the house.” Yet in managing his estate, in leading an army, in making landmark decisions as the first President, and in furthering the cause of freedom, Washington thought like a scientist. He was trained to look, to measure, to evaluate, and in doing so he acquired the capacity to re-formulate a hypothesis based on evidence. And as with any good scientist accepting peer review, he wrote, “I can bear to hear of imputed or real errors. The man who wishes to stand well in the opinion of others must do this, because he is thereby enabled to correct his faults.”

— Captain Scott Harris lives in Washington DC, and flies for a major airline based in Newark, NJ. He has logged nearly 10,000 hours of flight time, but when he’s not in the air, his favorite activities are terrestrial: playing the guitar, engaging in witty banter with his 12-year-old twins, and watching the Baltimore Orioles.