The negative results that improved healthcare for women

By Elizabeth Schiavoni, a freelance medical and science writer.

“The data was telling a story the public needed to hear…,” Dr. June Chang tells me as we discuss the groundbreaking clinical trial program she worked on throughout the early 1990s. “Thinking about it now, I’m getting excited.”

We’re speaking in the Health Sciences Library at the University at Buffalo about the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). In 1993, while Dr. Chang was pursuing a Master’s Degree in Epidemiology at Buffalo, the university was selected to be among the first sites for one of the largest medical studies of postmenopausal women ever conducted in the U.S. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) had launched the program two years earlier.

The Women’s Health Initiative started as a set of three clinical trials looking at the effects treatments like hormone therapy, diet modification, and vitamin supplements have on the most life-threatening conditions for postmenopausal women ages 50 to 79. Cardiovascular disease, cancer, and osteoporosis are among the major causes of illness and death in this previously understudied demographic.

Dr. Chang worked on the hotly debated hormone replacement therapy (HRT) study, one of two hormone therapy studies in the program, which had researchers and physicians divided. There were those who thought hormone treatments would “turn back the clock” on diseases afflicting older women, as Dr. Chang put it. And then there were those skeptical of replacing hormones like estrogen after menopause; Dr. Chang was one of the skeptics.

“I was in the category of people who really weren’t sure,” she said. “I can’t tell you how many women didn’t know what to do about hormone therapy because they were being told so many different things.” Since the 1800s, scientists have been intrigued by the idea of replacing decreased hormones (estrogen and progesterone) in menopausal women to improve quality of life and prevent disease. By the 1960s, physicians were prescribing this form of therapy regularly.

“In medicine, you can never be comfortable with what you learned last year.”

Between 1993 and 2005, the Buffalo site recruited almost 4,000 participants for the original studies on hormone therapy, diet modification, and dietary supplements. The Women’s Health Initiative as a whole would go on to include 40 sites and 160,000 women nationwide.

But, “the results were not as great as some people had hoped,” Dr. Chang said.

In 2002, investigators stopped the hormone replacement study early, because participants’ risk of getting breast cancer, strokes, and heart attacks had increased. The thought that hormone treatment would help with postmenopausal dementia did not pan out. What’s more, there was not enough evidence that dietary changes had anything more than a chance effect on cardiovascular disease.

“These were huge results,” she said. “The negative results had a marked impact on clinical practice.”

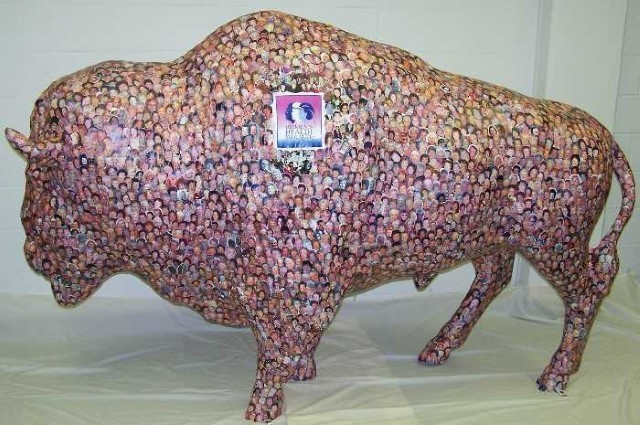

Photos of local WHI participants cover a statue of a buffalo at the University at Buffalo School of Public Health and Health Professions.

Now, healthcare professionals suggest women receive hormone replacement therapy (HRT) only for symptoms of menopause rather than for disease prevention, for the shortest time possible, at the lowest dose possible. After publication of the study’s findings, participation in HRT dropped by almost half. Dr. Chang noted that some researchers thought that the subsequent decrease in breast cancer might be due to less women getting hormonal therapy, and she cited a 2007 report in the New England Journal of Medicine. Along with contributing to a reduction in the use of HRT to treat chronic conditions and possibly decreasing breast cancer rates, a 2014 analysis showed the NIH’s investment in the hormone clinical trials resulted in a savings of $26.4 billion in healthcare costs alone.

Along with the program’s pluses, came the minuses. Most critiques of the Women’s Health Initiative had to do with study design. “Some thought more perimenopausal women should have been included,” Dr. Chang said. “Some thought the study should have run for much longer. There are always detractors because a study can always be designed better with information you didn’t have at the beginning.”

Dr. Chang has retired and moved on from her alma-mater, but the Women’s Health Initiative continues. Buffalo will participate in extension studies through 2020. Whether positive or negative results come out of those trials, one thing is for certain, they must, and will be broadcast to the public, as well as other clinicians and physicians. As Dr. Chang puts the importance of clinical trial transparency to her trainees: “…for the interest of their patients, they always have to be looking at new studies, even if you get busy as a clinician. In medicine, you can never be comfortable with what you learned last year.”

Dr. June Chang worked and taught at the University at Buffalo. Before retiring in 2016, she served as Chief of Geriatric Medicine at the Veterans Healthcare Administration of Western New York. The Women’s Health Initiative was launched in 1991 by Dr. Bernadine Healy, the first woman to lead the National Institutes of Health. The program regularly sends out national and Buffalo-specific participant newsletters, and makes a wealth of data from all their past and recent studies available on their website.