Suspicious supervisors and suspect surveys

Public opinion polls are ubiquitous in rich countries, especially during elections. Such polls estimate general support levels for political candidates based on the strength of their support within a small sample of that population. The classical ideal for building polling samples is that they should be random in the sense that each member of the general population has an equal chance to be selected into the sample and the selection of one member does not affect the selection chances of other members. These random samples are likely to resemble microcosms of the general population up to a margin of error that quantifies how unrepresentative of the whole the sample might be. In practice, real samples deviate considerably from this random ideal, because, to give one example, response rates are often lower than 50 percent, depending on the context.

Good survey researchers adjust their estimates to address such problems; for example, women are more likely than men to share their views with pollsters but both are equally likely to vote; so pollsters “count” men more than women in their surveys to mimic actual voting patterns. Adjusted polls have worked well during the ongoing U.S. primary elections, except for a spectacular failure in Michigan attributed in part to the under-sampling of younger voters.

Michigan was a huge, epic miss for the polls, but it’s weirder in some ways because the polls have otherwise been pretty darn good.

— Nate Silver (@NateSilver538) March 23, 2016

Another challenge facing pollsters is that survey workers, perhaps motivated by financial rewards for completed interviews or by a desire to minimize time spent in dangerous neighborhoods, may cheat by making up some of their data. Preventing data fabrication is a widely understood challenge among survey professionals that is seldom discussed publicly. A recent important paper finds widespread fabrication of one type—copying and pasting an observation into a dataset multiple times, possibly with slight alterations to evade detection. Humans have a long history of cheating opportunistically so it is hard to see why we would rise above this tendency when we become survey researchers; indeed, fabricating data could be a life saver for interviewers operating in war zones such as Iraq, where a survey author was murdered while going to work and interviewers in some areas proceed only by permission of local ISIS officials.

In 2011, Steve Koczela and I analyzed data from five polls in Iraq fielded by D3 Systems and KA Research Limited and sponsored by the Broadcasting Board of Governors and PIPA. We found evidence of extensive data fabrication in these polls. I give a flavor of this analysis in the next six paragraphs although space limitations only permit me to provide some suggestive anecdotes (interested readers should consult the original paper).

A couple of years before we met, Steve worked as a contractor for the State Department’s Office of Opinion Research on Iraq polling. He uncovered anomalies in the data collected by the State Department, some of which we later fleshed out in the paper, and which are described below. The source of the anomalies took some time to identify, because the literature on data fabrication that existed at the time tended to focus exclusively on interviewers, and patterns that might result from interviewer based fabrication. The idea of fabrication at the supervisor level, and methods that could be used to detect or confirm it were not mentioned in the literature.

The survey datasets provide a numerical code for the worker who conducted each interview as well as for his/her supervisor and the “keypuncher,” or data entry person who entered the data. Steve exploited this data feature to eventually settle on supervisors as the likely source of the anomalies and to find his way to a list of supervisors whose data showed patterns at odds with both typical survey data and with the data generated by the other supervisors. This group of suspicious supervisors[1] seemed to grow over time and consistently preside over non-credible interviews. All told, the suspicious supervisors we found account for about 30 percent of the interviews in the five surveys.

One phenomenon is that dozens of the questions offer choices that are not selected by any of the respondents for the suspicious supervisors. Such unanimity is exceedingly rare in real surveys and never happens for the non-suspicious supervisor group. A tiny example is that all 684 respondents to interviews presided over by the suspicious supervisors report owning a short-wave radio, compared to only around 40 percent short-wave ownership for the rest of the sample. On another question 105 respondents for the suspicious supervisors say that U.S. military withdrawal will cause violence to “increase a little,” 75 say it will “decrease a little” but zero say it will have “no effect either way.” Responses for the other supervisors are, respectively, 152, 187, and 42.

We can do a formal statistical test of the probability that zero out of 180 respondents for the suspicious supervisors will fail to offer the neutral response. A natural starting point for the test is to assume that the probability each respondent of the suspicious supervisors will select the neutral answer equals the fraction of the other 381 respondents who responded neutrally (42/381 = 0.11) and that this probability does not depend on how other people answer the question.

The chance that any one person does not pick the neutral response is then 1-0.11 = 0.89. The probability of 180 answers with no neutral ones is then 0.89 raised to the power 180 which is a negligible 0.0000000008. Moreover, this question is just one of dozens whose responses among surveys conducted by suspicious supervisors are not consistent with the responses among surveys conducted by unsuspicious supervisors. The full pattern of data looks virtually impossible, under the assumption that people interviewed by the suspicious supervisors were similar to those interviewed by the others.

Second, expected relationships between answers to pairs of questions do not hold for the interviews of the suspicious supervisors but do for the others. Indeed, all of the 684 respondents to the suspicious supervisors who report owning short-wave radios also report never listening to these radios. For the other supervisors the respondents owning short-wave radios report a wide range of listening hours, going from never listening to listening quite a bit.

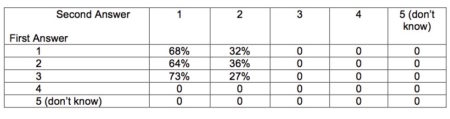

Another example of responses to pairs of questions suggesting fraud comes from a survey that asks essentially the same question twice: once at the beginning and again at the end of each interview.[2]The respondents of the suspicious supervisors exhibit virtually no connection between their early answers and their late ones (Table 1). It makes sense that 68 percent of those who answered 1 (very interested in the news) the first time around confirm their answer later. However, quite similar percentages of those answering either 2 (somewhat interested) or 3 (not very interested) the first time also go with 3 the second time (68% versus 64% versus 73%). In fact, zero out of the 122 people who answered with a 3 early in the survey confirmed their 3 at the end of the survey.[3]

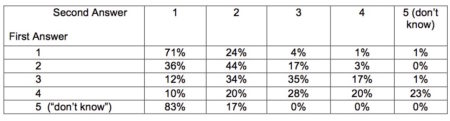

Table 1. Answers to the Same Question Asked Twice Table 2. Answers to the Same Question Asked Twice

– Suspicious Supervisors – Other Supervisors

Table 2 shows the relationship between answers to the same repeated questions for the respondents of the other supervisors. Now there is a clear connection between the two rounds of answers. For example, 71 percent of those answering 1 the first time repeat this answer the second time, while only 36 percent of those who first gave a 2 switched to 1 on the second round. Respondents who answered with a 3 the first time split evenly between 2’s and 3’s and had more 4’s than 1’s on the second round. The apparently bizarre jump up from “don’t know” to 1 applies only to 5 people and, in any case, it is not surprising that those without strong opinions can give almost any answer if they feel they must give a substantive answer to a question.[4]

We can quantify the above discussion through the calculation of a correlation coefficient that captures how predictive the answer the first time is to the answer the second time. A correlation coefficient of 1 would mean that the first answer perfectly predicts the second one whereas a 0 means that the first answer is useless for predicting the second. A correlation coefficient of -1 would mean that the second answer is always exactly opposite to the first. The correlation coefficients for these questions turn out to be -0.02 (useless for prediction) for the suspicious supervisors and 0.52 (fairly predictive) for the non-suspicious supervisors.

Other extraordinary patterns emerged from survey data on television viewing. One of the suspicious supervisors has a respondent who watches television between 20:30 and 21:00 (8:30-9pm), followed by the supervisor’s next household who watches from 21:00 to 21:30 (9-9:30pm), followed by the next one from 21:30 to 22:00 (9:30-10pm) straight through to midnight. These same households again switch on and off in half hour sequences at other times of day.

It is worth pausing at this point to consider whether we may have fallen into a technical trap. Any large dataset will have some strange anomalies. Perhaps a column of numbers gives your birthday three times in a row. Or maybe we see the answer 3 fifty times in a row. How do we know that we did not just stumble into a legitimate anomaly? We know because the suspicious supervisors show anomalies not just on a couple of questions but, rather, they display anomalies across many dozens of questions spread over multiple surveys.

We sent our paper out for comments, including to D3 Systems and other organizations behind the surveys we analyzed. D3 then tried to censor the paper by threatening to sue us. Langer Research Associates, which had claimed an Emmy Award and a Policy Impact Award based on other D3/KA-supported Iraq polling, backed this assault on academic freedom. The cease-and-desist letter stated that Langer had “conclusively determined that it [our paper] is false, misleading and asserts facts and conclusions that are incorrect.” My College-appointed lawyer wrote back requesting specifics so we could correct anything in the paper that was wrong but D3 and Langer did not reply.

Foolishly, I stayed silent until finally releasing the paper and the story at a recent conference. Shortly after that Langer Research Associates uploaded their old critique of my original paper. It has some interesting analysis without overturning any of the fundamentals. I treat this document in some detail on my blog but, briefly, its main point is that supervisors we did not identify as suspicious also have possible responses to questions that none of their respondents chose. This is true, but our suspicious supervisors have two to four times the number of missing categories compared to the others once you adjust for the number of respondents per supervisor. Moreover, nothing in the Langer report could explain the implausible relationships we found between answers to different questions or the bizarre television viewing patterns.

There were at least 20 polls fielded in Iraq by D3 and KA, including many sponsored by the U.S. State Department as well as those sponsored by a consortium of media outlets including ABC and the BBC. The award citation for the media work reads as follows

“The widespread, important impact of these polls on public knowledge and discourse and the thinking, deliberations and decisions of policy makers throughout the world is both indisputable and profound, a stellar example of high impact public opinion polling at its finest.”

Yet, based on the five polls we analyzed, it seems likely that at least some of these datasets are contaminated by fabrication.

Of course, even fabricated data could still be roughly in line with reality. Moreover, some inaccuracies, such as when people flip their television sets on and off, may not have substantive importance, although the U.S. government paid to collect these data. We need a bedrock of solid opinion data against which to compare the D3/KA results, as well as some information on how their polling data were used in order to conduct a proper damage assessment.

Fortunately, such a bedrock has arrived although we have not yet been able to analyze it. The State Department has just responded positively to a Freedom of Information request made by Steve Koczela back in 2010 by handing over a mountain of Iraq polling data, some collected by D3/KA and some by other contractors.

This is an extraordinary gift for research on Iraq and survey research more generally, not just for the work I have described in this article. Unfortunately, the media consortium continues to hold its data outside the public domain. This strategy of secrecy enforced by legal threats suggests that the data would not withstand scrutiny by independent analysts. I have placed my paper and the data in the public domain so anyone can check or challenge the work. The State Department has now released their data. It is time for the media consortium to follow suit.

—

[1] These are called “focal supervisors” in the original paper.

[2] The first time it is “How interested are you in staying informed about current events” and the second time it is it “Generally speaking, how interested would you say you are in current events?”

[3] Table 1 also shows the pattern discussed above of respondents to the suspicious supervisors not using the full range of possible answers. The first time the question is asked they use 1, 2 and 3 while the second time they only use 1 and 2.

[4] The rows in both tables do not necessarily sum to exactly 1 because of rounding.

Please note that this is a forum for statisticians and mathematicians to critically evaluate the design and statistical methods used in studies. The subjects (products, procedures, treatments, etc.) of the studies being evaluated are neither endorsed nor rejected by Sense About Science USA. We encourage readers to use these articles as a starting point to discuss better study design and statistical analysis. While we strive for factual accuracy in these posts, they should not be considered journalistic works, but rather pieces of academic writing.

“other 381 respondents who responded neutrally (42/391 = 0.11)”

You’ll get ~.11 using either 381 or 391, but I couldn’t help noticing the switch.