Are you a food addict? A major review of all the evidence by a consortium of European universities, which was funded by the European Union, concluded that the evidence that specific foods could trigger addiction was “poor;” but that the act of eating as a behavior could be addictive. Nevertheless, the concept of “food addiction” is still popular within science and in the media. “The scientific consensus is that food addiction is real,” according to UMass addiction psychiatrist Douglas Ziedonis; “sugar addiction and food addiction is one of the hottest new sciences emerging over the last 10 years, Dr. Pam Peeke told Maria Shriver in a recent NBC News feature. “What we’ve been able to find is that, in my estimation, heck yeah, it’s real.” How does she know? “We have a new tool that has been credentialed and published called the Yale Food Addiction Scale,” said Shriver. “And this is something that has been generated by scientists who are using a classic blueprint that we use in all addiction.” But as Rebecca Goldin explains in this updated article from STATS archive (originally posted on Oct 1 2013), the Yale Food Addiction Scale is deeply problematic.

Eating habits are a large part of most people’s lives; many cultures revolve around food, and our basic bodily needs require us to spend a couple hours daily thinking about food, if not consuming it. Yet clearly people abuse food – or abuse themselves by consuming too much food and drink. The Centers for Disease Control estimate that 69 percent of American adults are overweight or obese, with more than half obese.

Yet only recently has there been a focus on the possibility that people are addicted to food. Though the most recent psychological guidebook on disorders has not characterized overeating as a disorder itself, the push by both scientific and social interests to label the inability to eat less a problem of addiction is relentless.

MSNBC Morning Joe co-anchor Mika Brzezinski, whose book “Obsessed: America’s Food Addiction – and My Own” was published in May, explained on the Huffington Post, “I’m not afraid to say I am addicted to certain foods. To me, addiction is the right word: the one that fits the pattern of my behavior and helps to explain some of the poor choices I have made.”

New York Times reporter Michael Moss told readers of the paper about “The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food,” – an extract from his book Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us, which went on to become a bestseller.

And Dr. Pamela Peeke invited visitors to Fox News.com to take her diagnostic quiz to determine whether they were food addicts. “This is a special assessment developed by Yale University researchers to evaluate your relationship with food. Experts believe that the majority of people who are overweight or obese have some level of food addiction. However, anyone of any age and size can have this issue.”

The meaning of addiction

No doubt many people do eat too much. But the question is when to label the relationship between people and the food they eat addictive. After all, unlike heroin, cocaine, alcohol and tobacco, food is a substance from which we cannot abstain. So, when does a line get crossed into the realm of addiction? In other words, what does addiction mean? According to American Society of Addiction Medicine:

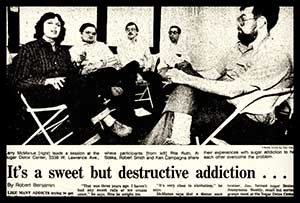

“These are the sugar freaks. They may have started as children with candy and pop, but they have become adults trapped in a sucrose cage, usually a big one. And it isn’t funny” — from the April 29, 1982 edition of The Chicago Tribune on Sugar Beaters Anonymous Weekly.

The idea of food addiction, far from being something new, was first proposed by T.G. Randolph in a 1956 paper, “The descriptive features of food addiction; addictive eating and drinking.” Unsurprisingly, it gained ground in the US in the early 1970s, as drug addiction captured the headlines and anxieties of the nation. Yet the emphasis in the 1970s is more on overeating as a compulsive behavior rather than specific food items, which, ironically, something that is identified in the European review of the scientific literature. As The Chicago Tribune noted on September 1, 1975, in a story by Christine Winter on a woman who had joined Overeaters Anonymous: “I couldn’t cope with my feelings,” she said, “so I ate them” —Trevor Butterworth

“Addiction is a primary, chronic disease of brain reward, motivation, memory and related circuitry. Dysfunction in these circuits leads to characteristic biological, psychological, social and spiritual manifestations. This is reflected in an individual pathologically pursuing reward and/or relief by substance use and other behaviors. Addiction is characterized by inability to consistently abstain, impairment in behavioral control, craving, diminished recognition of significant problems with one’s behaviors and interpersonal relationships, and a dysfunctional emotional response. Like other chronic diseases, addiction often involves cycles of relapse and remission. Without treatment or engagement in recovery activities, addiction is progressive and can result in disability or premature death.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse has a simpler explanation:

“Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing brain disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite harmful consequences. It is considered a brain disease because drugs change the brain; they change its structure and how it works. These brain changes can be long lasting and can lead to many harmful, often self-destructive, behaviors.”

Diagnosis is a complicated issue fraught with shades of gray. An alcoholic may arrive at the doctor’s office drinking cough syrup and suffering from fatty liver, or he may simply need a steady supply of vodka to function sufficiently at work, while burning bridges in his personal life. Regardless of how drug addiction presents, medical professionals (including psychologists) have long recognized the need for identifying those with alcohol addiction before they’re about to succumb to liver failure, and cocaine addicts before they overdose. A diagnosis is often attained by scoring an individual on an assortment of “tests:” Someone is only diagnosed with alcoholism, for example, when he or she meets the criteria spelled out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). These include experiencing three or more of the following symptoms (listed at the Mayo Clinic) in any 12-month period:

- Tolerance (typically, an increase),

- Withdrawal symptoms when you cut down or stop using alcohol.

- Drinking more alcohol than you intended or drinking over a longer period of time than you intended.

- Having an ongoing desire to cut down on how much you drink or making unsuccessful attempts to do so.

- Spending a good deal of time drinking, getting alcohol or recovering from alcohol use.

- Giving up important activities, including social, occupational or recreational activities.

- Continuing to use alcohol even though you know it’s causing physical and psychological problems.

Surveys have been developed to measure the existence of these problems, and they have been used to diagnose millions of people in the U.S. alone.

But the question of how such criteria can be applied to people with destructive relationships to food is fraught with problems. Though the most recent DSM 5 (released in May, 2013) does not recognize food addiction as a disorder, some psychologists responded with their own survey purporting to measure food addiction.

The Yale Food Addiction Scale – mentioned by Dr. Peeke – asks individuals to rate the frequency in which they experience certain “unhealthy” relationships to food. It is modeled on the addiction measurements described in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV-R for drugs, with the proposal that, in some circumstances, people behave toward food as they do toward drugs.

The spirit of such a questionnaire is admirable, and it has been shown in small studies to be predictive of known eating disorders (such as binging). But the questionnaire could easily over-classify food addiction in quite obvious ways, revealed by a close look at the survey questions and scoring techniques.

The technicalities of the Yale Food Addiction Scale

The questionnaire is graded based on a respondent’s answers to 27 questions, of which 22 “count” toward a score. The questions measure the frequency with which one participates in behaviors that suggest addiction. Much like the alcohol dependence list above, the scoring of the questionnaire turns answers into general observations such as whether a person has withdrawal symptoms or spends too much time eating. The full questionnaire is readily available to the public, as is its scoring instructions. The problem lies in part by how easily, on a massive scale, non-addictive behavior can be translated into an “addiction.” In other words, it’s not clear what the test is measuring.

The YFAS is designed to correlate with destructive eating disorders like binge eating. On their scoring technique, the authors acknowledge their motive quite freely: “The goal was to identify cut-offs that were most clearly associated with increased risk for eating pathology.” It is not a surprise, then, that the YFAS is highly correlated with an increased risk of eating pathologies as measured by other psychometric tests and physiological tests like body mass index.

A diagnosis of “addicted” or “not addicted” can be maddening black or white with no shades of gray, but the ease with which one can be diagnosed is telling.

Here’s how food addiction is identified: A person who experiences some amount of distress over their behavior with food, or has problems in their daily routine due to food and eating is considered a food addict if, in addition to the distress, three of the following criteria are met within a year:

- Taking in larger amounts or for a longer duration

- Persistent desire or repeated unsuccessful attempts to quit

- Withdrawal Symptoms

- Excessive time spent pursuing, using, or recovering from use

- Reduction/discontinuation of important activities because of use

- Tolerance

- Continued use despite consequences.

While the symptoms are parallel to those of alcoholism or drug use, a closer look at the design of the questions suggest otherwise.

Withdrawal symptoms

Consider the criterion “withdrawal symptoms”. People with alcohol dependence exhibit a variety of different symptoms when they stop drinking, from anxiety to convulsions. These people may shake when they go without a drink, or wake up and needing a drink to start the day or concentrate.

“The effect of sugar addiction on the brain has been seen now in both clinical—trials, as well as in animal work that we have done in the laboratory,” Dr. Pam Peeke tells NBC News. “What we see (in the reward center of the brain) are identical, indistinguishable changes between sugar or food addiction and any other addiction, for instance, cocaine, methamphetamine, morphine, alcohol.”

But in the European study, ‘ “Eating addiction’, rather than ‘food addiction’, better captures addictive-like eating behavior,” the authors note that “apart from a single case study (Thornley and McRobbie, 2009), addiction-related behaviors in sugar consumption (such as tolerance and a withdrawal syndrome) have not been observed in humans (Benton, 2010). Instead, most observational and mechanistic evidence for addiction to sugar comes from rat models…”

The findings from these models are far more complex, due to the interaction with behavior, than the claim that sugar acts just like cocaine suggests; moreover, the authors note that the rats do not become obese in most of these sugar addiction models, as they “down-regulate their energy intake from other sources and maintain a stable body weight (Avena et al., 2012)… [this leads] to the hypothesis that sugar addiction in humans—if it occurs at all—may not be relevant for the development of obesity. Since normal food intake is reduced after binges and weight gain does not occur, homeostatic mechanisms are preserved, it could be argued that these paradigms may better represent a form of binge-eating driven by intermittent access to hedonic stimuli” — Trevor Butterworth

While these questions seem descriptive enough, a contrast with alcohol here is useful. If someone experiences and elevated desire or has an urge to drink when he or she cuts down on drinking, it certainly does suggest that their body “needs” alcohol in a way that someone who is not at all dependent wouldn’t demonstrate. But we pretty much all desire food. The questionnaire is trying to get at something partial, an “elevated desire,” i.e., more than usual, for “certain foods.” Here we get into the murky territory of individual variation even in healthy realms of eating. Most dieters have trouble with elevated desires for chocolate cake – or perhaps a glass of wine – or maybe it’s just a sandwich with bread instead of a salad. After all, dieters are purposefully denying themselves either the quantity or the substance of what they normally eat. Are all dieters automatically meeting the criterion of “withdrawal symptoms,” making them one step too closer to an addiction diagnosis?

But this brings up the possibility of under-diagnosis of “withdrawal symptoms” as well; for only people who would meet the criteria for “withdrawal symptoms” through urges are attempting to restrict their eating. Those who eat to their hearts’ content, without worry for the implications in other parts of their lives, will not experience withdrawal. This under-diagnosis of an effect that might be present should the person try to stop eating could be similar to the same effect among people who have alcohol dependence.

For someone who isn’t dieting, meeting the clinical definition of suffering withdrawal can also be met in another way: at least twice per week one has “consumed certain foods to prevent feelings of anxiety, agitation, or other physical symptoms that were developing.” How does hunger mollified by a donut fit into this? How does anxiety about work being calmed by a good breakfast fit in? How does having a cookie because it makes you feel better after a fight with your ex-spouse (and an oncoming feeling of agitation) play into a possible dependence diagnosis?

Needless to say, withdrawal symptoms alone do not qualify one for a diagnosis of food addiction. But it does point to the ease with which a diagnosis can occur. And the contrast with the same questions/symptoms around the use of alcohol is striking. Craving food is normal and hardwired. Craving alcohol is typically not acquired at birth. Needing food is essential for survival. Needing alcohol is a sign of addiction.

The close relationship between dieting and addiction

The questionnaire on food addiction seems to entrap dieters in more ways than just equating cravings with withdrawal. Consider the symptom “Persistent desire or repeated unsuccessful attempts to quit.” Presumably, by “quit” the authors mean “quit overeating” or something similar, but we can examine the questions whose answers impact this score. There are 4 questions with answers that can lead to a diagnosis of meeting the “withdrawal symptoms” criterion. They are:

- “Not eating certain types of food or cutting down on certain types of food is something I worry about” (4 or more times per week)

- “I want to cut down or stop eating certain kinds of food.” (yes)

- “I have been successful at cutting down or not eating these kinds of food” (no)

- “How many times in the past year did you try to cut down or stop eating certain foods altogether?” (5 or more times)

Note that one cannot answer the question of whether one has been successful at cutting down or not eating “these kinds of food,” when he or she didn’t try to cut down on them.

The criterion is met if any of the answers above are as specified to these questions. And here is where we can see how easily one might meet the criterion of “persistent desire”. Essentially any dieter or simply health-conscious adult will meet the criteria of “wanting to cut down” on some kinds of food. It’s hard to see why this is part of the calculus at all.

Yet if it were alcohol, the analogous questions would be far more appropriate and may be an indicator of a problem. For trying and failing to stop drinking may well be an indicator of dependence; but does trying and failing to diet suggest dependence in the same way? (For sure, we are all dependent on food – it’s the negative impacts that health professionals are concerned with).

Other criteria are also easily met – and so a score of greater than or equal to three on the Yale Food Addiction Scale is easily attained.

Yet a score that is parallel to that of substance dependence (interpreted here as addiction) requires also the existence of adverse consequences of one’s relationship to food. The final required criterion is that of “clinical significance.” One must experience one of these symptoms at least twice a week:

- Behavior with respect to food and eating causes significant distress, or

- Significant problems in ability to function effectively (daily routine, job/school, social activities, family activities, health difficulties) because of food and eating.

Perhaps these last qualities are the reason that only 11.6 percent of the 233 interviewed college students used to validate the study met the criteria to be “food dependent”. While the authors felt this percentage is consistent with the percentage of students meeting clinical cut-off for the Binge Eating Scale (BES) and the Eating Troubles Module (EAT-26), the small and homogeneous sample with very low obesity rates (2.7 percent) leave room for more questions about the validity of the test and what can really be concluded by scoring positive for food addiction.

Food versus drugs

The way that food affects our minds is complex and understudied, but there is an obvious and stark contrast between alcohol/drug use and food use: food is required for human life. This elephant in the room has a significant and clinical impact on the way “food addiction” is diagnosed according to the now widely accepted Yale Food Addiction Scale. The test itself may have some useful clinical application for overweight and obese people – it could be the starting point for someone to work through issues that could be impacting their ability to lose weight – but an addiction should require a stronger threshold, including one that involves a specific substance or combination of substances to which some people respond in a fashion parallel to illicit drugs.

The reality for food addiction as defined is that it’s not as predictive as one might hope. Obese and overweight people are more likely to suffer from “food addiction,” but underweight and normal weight people also meet the criteria. So the question really becomes: what significance or value does the “diagnosis” add to the discussion about helping people live healthier lives?

The authors of the food addiction scale hope that the metric is used to help people frame the debate about our relationship to food—and certainly unhealthy relationship abound. But the consequence of labeling someone “addicted,” when the neurological framework isn’t present, when there is no hope of abstinence, when there are many overlapping pathologies, is certainly at question. For a typical obese person trying to shed pounds, a diagnosis of addiction may remove the agency in making food choices and cast blame toward food providers, rather than offering solutions based on a diagnosed problem. And where’s the benefit of that?

The Yale Food Addiction Scale have instructions:

Copied from the Scale:

“This survey asks about your eating habits in the past year. People sometimes have difficulty controlling their intake of certain foods such as:

– Sweets like ice cream, chocolate, doughnuts, cookies, cake, candy, ice cream

– Starches like white bread, rolls, pasta, and rice

– Salty snacks like chips, pretzels, and crackers

– Fatty foods like steak, bacon, hamburgers, cheeseburgers, pizza, and French fries

– Sugary drinks like soda pop

When the following questions ask about “CERTAIN FOODS” please think of ANY food similar to those listed in the food group or ANY OTHER foods you have had a problem with in the past year” (Gearhardt et al., 2009).

It’s not a questionaire about the foods that we need to survive, it’s about the “food products”, different of real food. This are not real food, this are ultraprocessed foods, that enrich your food envoirment, and the binge occurs whith this “type of foods.

I agree that the survey asks about foods that are not necessary for survival. In fact, one could avoid many types of food and still survive. It also asks, as you point out, whether the behaviors tested pertain to “ANY OTHER” foods. In effect, while the questions prime the readers to respond specifically with regard to the “certain foods” listed, it explicitly requests that readers record whether they have experienced the symptoms with regard any other foods.

Additionally, while it is true that the “certain foods” listed are not required for survival, it is also true that these are the foods do, in practice, serve to nourish people. For many people, these are the foods available and affordable to them, and what constitutes “food”. Their responses to these foods—such as trying and failing to resist them, overeating them, or simply desiring them more than necessary for their bodies—are not per se indications of an “addiction” the way the same response to alcohol would be.

The evaluation of the survey turns a dieter into an addict; the high level of pathology diagnosed among a population with a low incidence of obesity reflects the broad sweep with which this survey diagnoses addiction.

Two major issues I take with this. First, as mentioned already it is addiction to certain types of food that is critical here. I’d like to amend this label to read “junk-food addiction”. Chocolate cake can have negative effects on health and you can live without chocolate cake, making abstinence absolutely attainable. The second is that your assuming that only obese people are going to have health issues. Blood pressure, LDL to HDL ratios, fasting insulin level, heart rate, urine microalbumin level, and other health markers can all be out of whack even for someone with no visible outward signs of poor health. Acknowledging presence of an addiction, especially in those of normal weight, may well indicate the possibility of other comorbidities that would otherwise go unnoticed.

You’ve made a common but inaccurate correlation between “food addiction”, “obesity”, and “health”. The addiction, in my experience, is characterized by the obsession surrounding the substance or behavior, which is often associated with depression, anxiety, PTSD, or other mental health disorders – none of which have anything to do with obesity but a great deal to do with health. Since the obsession seems to be the hallmark of the addiction, a person “controlling” the addiction through serial dieting (or other measures) may well be of normal weight, but riddled with depression and anxiety as taming that addiction feels like wrestling a giant, slithery, slippery snake. Furthermore, serial dieting does seem to suggest a more significant unhealthy relationship with food. Whether we are comfortable using the term “addiction” is irrelevant, as this survey can help us identify underlying issues with body image and self esteem, and further help us as a society, be more conscious of the deleterious of normalizing junk food.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1QoVpetAOY

This is very informative and gives greater explanation as to how and why the YFAS is indeed significant.